In Nigeria’s continuously evolving music landscape, the traditional divide between gospel and secular music is becoming increasingly difficult to define. As artists move fluidly between faith-inspired expression and mainstream success, the question is no longer whether gospel and secular can coexist – but whether the line ever truly existed.

In Romans 12:2, the apostle Paul urges Christians to resist the pressures of the world and renew their minds according to God’s truth. For many believers, this means distancing themselves from secular culture and secular music , one that favors prayer, fasting, and worship that centres God.

For decades, the divide between gospel and secular music in Nigeria mirrored this spiritual boundary.

But today, that line is no longer as clear.

Over the years, Nigerian music has been shaped by one of the country’s deepest cultural tensions: the divide between gospel artistes and secular artistes. The church, morality, and communal expectations drew a clear line between those who ministered from the pulpit and those who entertained with sonic rebellion. Yet in 2025, this line has thinned, blurred, and – some would argue – almost dissolved.

The shift has been gradual but undeniable. When Victor Thompson remixed This Year (Blessings) which brought together gospel artist Ehis ‘D’ Greatest and rapper Gunna in 2023, or when Tim Godfrey collaborated with Oxlade ( known for his hit “Kulosa.” ) on Infinity in 2025, something fundamental changed, that line is blurring.

These collaborations reveal a new terrain where gospel artistes and secular artists no longer occupy separate worlds but weave their styles together, creating something harder to categorize.

These were not simple collaborations; they were cultural signals. They revealed a music ecosystem where gospel and secular are no longer opposites, but overlapping spheres of influence, sound, and commercial demand.

To understand how we got here, it helps to revisit the origins. Gospel music in Nigeria began not as entertainment but as ministry, how it imported through missionaries and later reshaped by pioneers like Reverend Josiah Ransome-Kuti, who infused Yoruba rhythms and indigenous storytelling into worship.

Secular music, however, evolved from traditional entertainment, Islamic-rooted genres like fuji and apala, satirical folk forms, and the street-level dynamism that would later birth Afrobeats. The boundaries were clear: gospel was sacred; secular was social.

But the 2010s disrupted the old order. Afro-adura emerged, one that is a fusion where prayer meets percussion. Artists like Asake and Seyi Vibez sprinkled spiritual intros and biblical references into club-ready records. Anendlessocean defied categorization altogether, choosing to identify as a Christian artist rather than a gospel one.

Across the diaspora, artists like DC3 and Caleb Gordon infused drill and hip-hop aesthetics with devotional content, blurring genres even further.

Nigeria’s religious identity complicates this evolution. The average Nigerian lives in prayer before meals, in traffic, during hardship, and even at the club. Music mirrors this lived spirituality. Secular artists now lean into religious language not necessarily as doctrine but as cultural resonance.

Meanwhile, gospel artistes adopt high-production visuals, brand partnerships, digital strategy, and pop-star aesthetics once reserved for mainstream acts. The audience welcomes this fluidity, streaming gospel and secular side by side without friction.

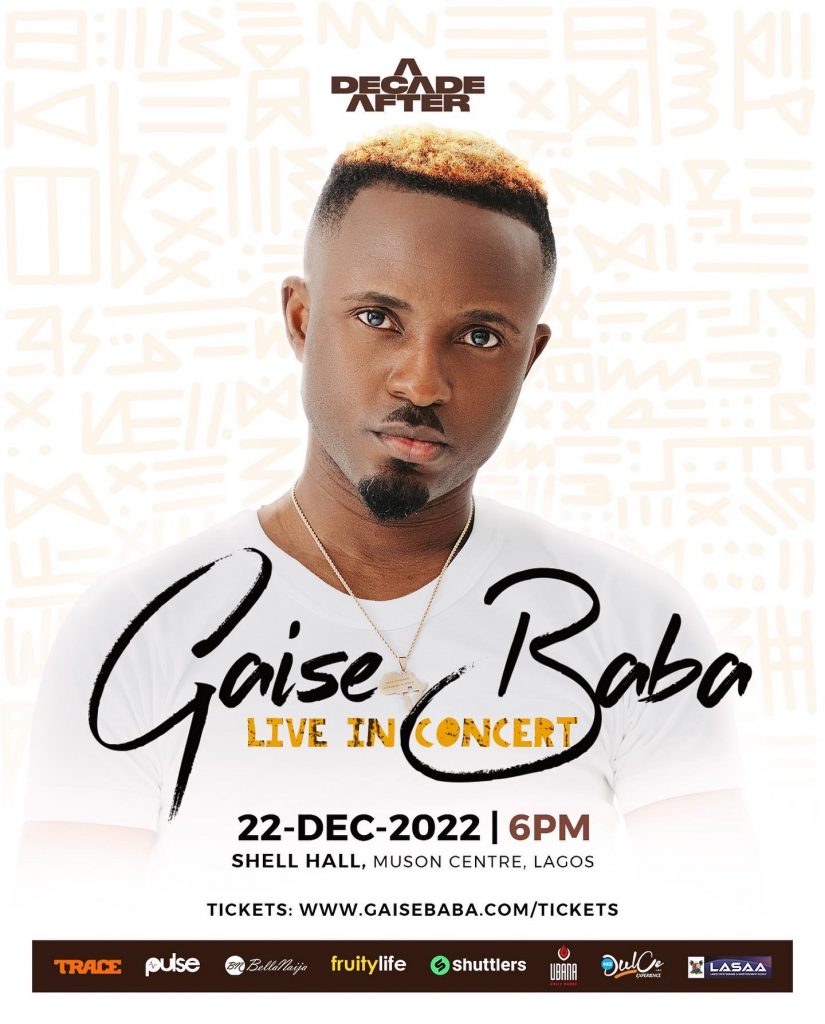

Commercialization has played its part. Gospel music is now streamed, monetized, marketed, and promoted with the same machinery as Afrobeats. Ticketed concerts like Gaise Baba’s 2022 show, premium seating tiers, sponsorships, and brand integration reveal a business ecosystem indistinguishable from the secular world.

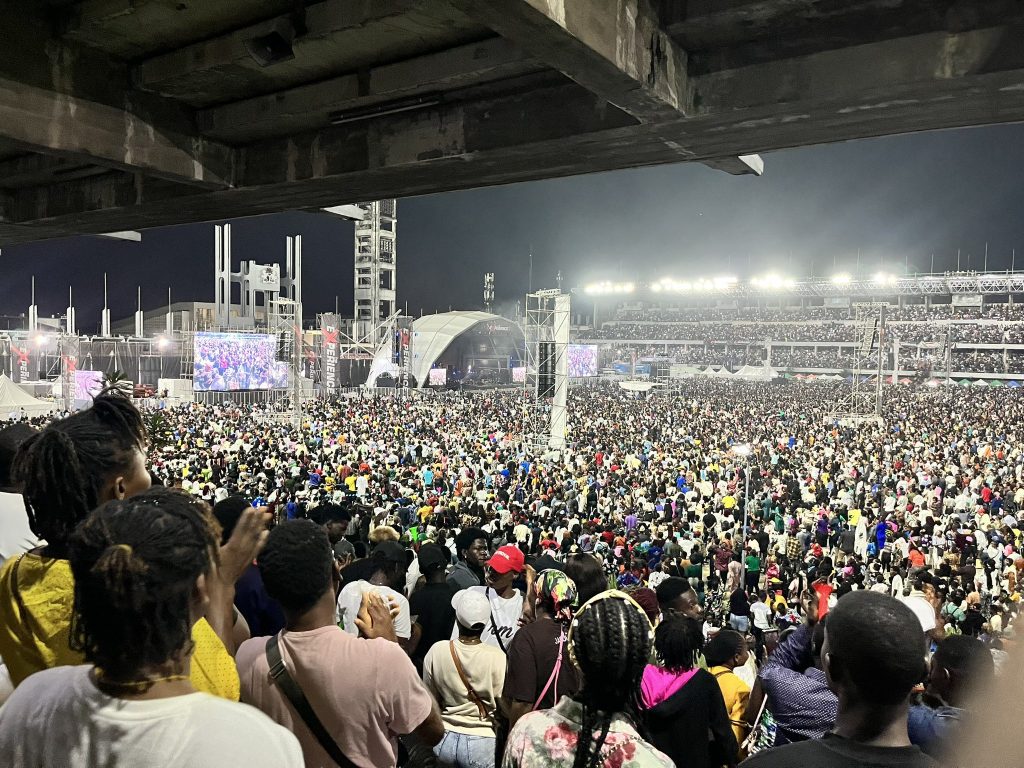

Even free-access shows like The Experience operate on million-dollar budgets, quietly sustained through church networks and philanthropy.

So what truly separates gospel and secular artistes today? Certainly not sound, visual aesthetics, or performance culture. The difference now lies in intention, identity, and accountability. Gospel music remains anchored in a spiritual mission; Christ-centered messaging, ministry, and transformative purpose. Secular music, though capable of referencing God or philosophy, is not obligated to evangelize. Its freedom is creative, emotional, and experiential rather than doctrinal.

And then there’s accountability: gospel artistes answer to faith communities, pastors, and doctrinal scrutiny, while secular artistes answer to charts, fans, and labels.

But even this distinction is strained when gospel artistes adopt mainstream branding or performance styles that echo pop culture aesthetics.

After tracing this long arc of history, the answer is layered. Yes of course the lines are blurred. Sonically and visually, the two worlds often look identical. Commercially, they inhabit the same machinery.

Culturally, their audiences now overlap seamlessly. Yet, the difference still exists – thinner, but alive. It rests not on genre labels but on the integrity and conviction of the artiste.

The future of Nigerian music might not be a clear binary between gospel and secular, but a spectrum. And on that spectrum, what matters most is not how the music sounds, but what it stands for.

Guest written by Olumuyiwa Aderemi

Curated & Edited by Music Custodian.